Dogs, like any animal, are susceptible to soft tissue, muscular injury throughout the course of their everyday activities. Most soft tissue injuries in dogs are due to falls, fights, accidents, and during exercise and play. Our blog about muscular injury in dogs discusses the science behind the phases of muscle healing and repair.

Categories of muscle tearing

A soft tissue muscular injury can be categorised according to the extent of muscle tear.

The three levels of muscular injury are:

Stage 1

Relatively minor. There is some shearing of the muscle fibre – a 20-30% muscle tear.

Stage 2

More problematic and the most painful. 30-90% of the muscle fibres have been broken.

Stage 3

Total tear. Less painful than Stage 2 due to nerve endings also having been severed.

Phases of muscle injury healing and repair

Wound healing refers to the body’s replacement of destroyed tissue with living tissue. All injuries to connective tissue, and muscle is no exception, must undergo the same healing process, regardless of their severity.

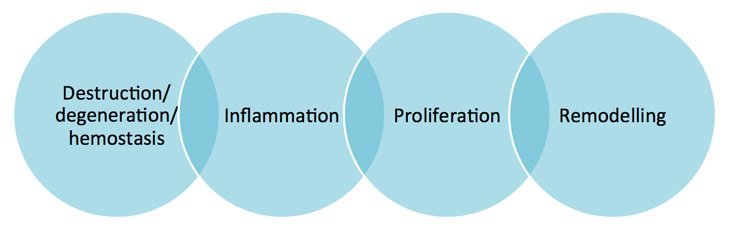

Muscle healing and repair is a complicated process, which is divided into four overlapping, interlinked phases.

Destruction – degeneration – hemostasis

Trauma to muscle tissue following an injury will result in mechanical damage to the muscle fibres, destroying the integrity of the muscle cells and their components. The muscle fibres become cut off from their nerve supply.

The initial rupture is followed by the death of muscle fibres both in the damaged tissue and in the adjacent healthy tissue.

The process of hemostasis then begins. This is a response by the body to stop the flow of blood at the injury site and to seal the damaged blood vessels. Blood vessels immediately constrict in response to the injury. Blood clots are also formed.

Inflammation

Usually lasting up to four days after injury, inflammation is the body’s early reaction to muscle tissue trauma and involves coordination between the immune system and the damaged tissue. Inflammation also prepares the injured tissue for the phases of tissue repair that follow. You will notice that the skin will redden due to the dilation of small blood vessels. There will also be swelling, warmth and pain (which indicates that the immune response to the injury is working as it should).

The body produces various chemicals in response to inflammation. These substances work to eliminate toxins and to begin preparing the damaged muscle fibres and blood vessels for regrowth in the area.

Proliferation

The proliferative phase is the stage when cells produce the materials to repair the injury. It involves the production of scar tissue, and commences after 2-3 days and is generally completed 2-3 weeks after injury.

Proliferation is divided into two sub-processes – the formation of collagen, and the formation of new blood vessels.

The regeneration of muscle fibres is also a function of the proliferation process. In addition, the regeneration of intramuscular nerves is also necessary, as a lack of reinnervation of the muscle fibres results in atrophy. Muscle fibre regeneration is generally achieved within 3 weeks.

Remodelling

The remodelling phase is the next period of muscle repair (usually 2-3 weeks after injury) where the body tries to restructure the injury site back to the pre-injury state.

During remodelling, any muscle fibres that survived the initial trauma will form branches and will also try to penetrate through the scar tissue on either side. The branches adhere to the scar and form mini-muscle tendon junctions, which help to increase the overall strength of the scar, making it stronger than the adjacent muscle fibres. Furthermore, lateral branches also form to reduce the movement of the damaged muscle fibres, reducing the pull on the delicate scar.

Overtime the scar progressively diminishes and contracts, and the muscle fibres become interlaced. The strength of the tissue improves, and the functional capacity of the muscle is reestablished. Once the muscle is being used normally, the scar will steadily mature, eventually resembling the pre-injury tissue.

Remodelling continues for many months and may take up to two years after injury.

Sources

- Cole, L., 2010. How to Handle Soft Tissue Injuries in Dogs. Available at: http://www.canidae.com/blog/2010/03/how-to-handle-soft-tissue-injuries-in-dogs.html.

- Relaix, F., Zammit, P.S., 2012. Satellite cells are essential for skeletal muscle regeneration: the cell on the edge returns centre stage. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22833472.

- Slavin, T., n.d. The Process of Inflammation and Repair at Cellular Level and Implications for Sports Massage Practitioners. Available at: http://www.advancedbodyworks.co.uk/docs/inflammation.pdf